Connection of Fashion and Disability: Why Does Fashion Matter to Disabled People?

“Deaf voices go missing like sound in space” (Antrobus, 2018) as stated by deaf poet, Raymond Antrobus. The following statement is one that rings true across the board; those with a hidden disability are often overlooked in society. A statement relevant to the fashion industry, specifically those within the industry that may have a hidden disability.

This essay seeks to explore the different reasons as why fashion is important amongst those in the disabled community. To investigate this importance, firstly, I define fashion as ‘Fashion includes the industry that surrounds the clothes themselves and the way in which fashion and disabilities are represented’. Examples I have chosen to illustrate this is Aimee Mullins’ Alexander McQueen SS1999, Alison Lapper’s sculpture in the 4th plinth, Unhidden Clothing, and Tommy Hilfiger’s Adaptative line.

To unpack the importance of fashion for disabled people, it’s important to understand what fashion is; “Fashion is defined as products worn on the body through which human beings non-verbally communicate a define cultural aesthetics.” (Annett-Hitchcock, 2024). It is also important to understand what the term disability means. Disability, in the context of this essay is “any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions)” (CDC 2020). My essay will explore the representation of disability within fashion.

This topic is of interest to me as someone who considers themselves part of the disability community. I have been diagnosed with postural tachycardia syndrome, epilepsy, and most importantly, I am hard of hearing. I feel that my personal experience allows me to read and interpret the examples from the perspective of those fashion consumers who are overlooked in the industry, from the perspective of both the fashion consumer and the disabled.

Fashion is often associated with identity and empowerment; this is particularly important amongst the disabled community whom may struggle with identity and empowerment, “The process of identity construction relies on the meanings associated with our clothes. These meanings might relate to the style of the garment, in terms of its silhouette, detail or material, or to the designer or manufacturer, as communicated via […] branding.” (Twigger, 2017). The clothes we choose to wear contribute to how we express and define ourselves to others and to ourselves.

Fashion can also be used as a tool for self-expression for disabled people. In a YouTube video I watched by Jessica Kellgren-Fozard, she commented, “When you’re in a wheelchair, walking with a stick or looking slightly like a fool because you kind of missed what’s on earth going on in this conversation now, because you can’t hear… people are going to look at you anyway so you should give them something to look at.” This suggests that society tends to look or stare at people that seem “different” whether that is a good that or bad thing. Fashion can empower people, abled or disabled, but it can make disabled people feel more comfortable instead of feeling singled out. Kellgren-Fozard further explained that “how welook isn’t important in terms of our own identity and how we feel about ourselves. It also impacts how other people look at us and see us and react to us.” It isn’t just important for disabled people to feel good comfortable about themselves, for some it’s also important that they feel like they fit in.

Clothing plays a crucial role in shaping one’s sense of belong with different social groups or communities. People often use close as a medium of self-expression and identity. When individuals feel that their clothing aligns with the norms and values of a particular society, they are more likely to feel included within that community. “Having the right clothing can include or exclude people from communities, opportunities and participation in important life experiences, which affects their well-being (Adam and Galinsky 2012). This explains that clothing can influence opportunities for participation in important life experiences such as education, employment, social event, and recreational activities. In many cases, certain dress codes or expectations may dictate what is considered appropriate attire for these occasions. If disabled people do not have access to clothing that meets these expectations, they may face barriers to participations and miss out on valuable opportunities for personal and professional growth.

Fashion mirrors civil rights movements’ impact, advocating for equality, representation, and social change in contemporary society. Annett-Hitchcock explained, ‘In most parts of the world, we have rights granted to us as citizens of a country. If those rights include the freedom to self-actualize and to enjoy equality with other citizens, then fashion, with its ability to communicate our personal style and values in a non-verbal way, is a tool for communicating and celebrating those rights.’ (Annett-Hitchcock, 2024). This statement emphasizes the intersection of fashion, personal expression, and rights as citizens. It suggests that in many societies, individuals are granted certain rights and freedoms as citizens, including the right to self-actualize and the right to equality with others. Fashion, with its unique ability to convey personal style and values through non-verbal means, is portrayed as a powerful tool for expressing and celebrating these rights.

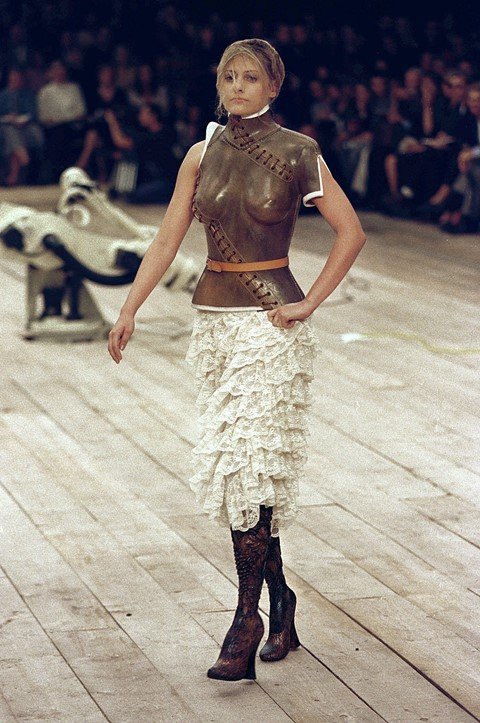

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows Aimee Mullins who is a model, athlete and an activist during the Alexander McQueen ready-to-wear SS1999 London Fashion Week show on September 27th 1998. She is also a double amputee. Mullins was a trailblazer; she pioneered the recognition within the fashion industry that individuals with disabilities also deserve stylish options.

Figure 2

Tommy Hilfiger has an adaptive line for children and adults. The website explains how Hilfiger embraced everyone affected by a disabled individual’s needs. The website is designed so customers can shop by categories that suits their needs; Easy closures (including magnetic buttons, Velcro, “one-handed” magnetic zippers), Fits for Prosthetics, Comfort and Seated Wear, Port accessible, Ease of Dressing, and Wheelchair friendly. Hilfiger’s himself has children on the autistic spectrum and his sister had Multiple Sclerosis. He created this line as he has some understanding of how hard it can be to dress yourself because he had someone that went through that experience, suggesting that people only start to make change and become more inclusive through personal experience or knowing someone that experienced it. This demonstrates the fashion industry’s lack of awareness, and there wouldn’t be as much growth in the industry until they become aware of the struggles. People’s motivation for inclusivity in Fashion stems from personal engagement with disability, they build upon their experience and use their skills to advance the field and produce fashion.

Unhidden Clothing is another brand that does adaptable clothing; where Hilfiger create clothes for both abled and disabled people, Unhidden create garments catered towards just disabled people. Unhidden is a high-profile adaptable clothing brand; they were part of the London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2023 and was featured in press including The Guardian and British Vogue. This illustrates societal progress towards greater inclusivity and representation.

In the Vogue article, “Why Disability Representation is Crucial to Building a Better, more inclusive Fashion Industry” by Madison Lawson, who explained “It isn’t just about representing disability in the media but also employing them and allowing them and allowing them to have equal opportunities in the industry”. The article was written by a disabled journalist giving disabled community a space to voice their experience. Although the media is able to create a discourse and persuade the audience into agreeing with what they choose to discuss, to say that it was written by a disabled journalist not an abled bodied, allows Vogue to show an honest story. Since they’re such an influential fashion publishing media regardless whether they were genuine or not, they are able to make an impact. However, it wasn’t until 2019, they included their first physically disabled model on their front cover, Sinead Burke. Also, “[…] employed a keyword search using numbers of terms including “disability” and “disabled” […] But not all reporting on the importance of representation was expansive […] Teen Vogue rarely discussed the representation of disability in terms explicitly related to style or fashion.” (Brown, Marato, and Pettinicchio, 2024) This could indicate a gap in representation within Vogue’s coverage highlighting an area where the publication could potentially improve its inclusivity and diversity efforts.

Annett-Hitchcock talks about that its only since around 2010 that global mass-market fashion industry starting to take notice of disabled people.

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows an ASOS campaign featuring disabled model but also worked with Chloe- Ball Hopkins, a wheelchair user, to design fashionable, practical waterproof jumpsuits. There is a zipper between the jacket and the trousers so wheelchair users can easily undress themselves to use the toilet. Barry and Christel summarised “[…] it is urgent to have more design courses that truly include disabled people as collaborators and creative makers.” (Barry and Christel, 2023). They further explain, “[…] implementing inclusive design is more complex than simply designing with disabled people in mind. It often fails to treat disabled people as equalled, sometimes disempowering them to have real agency on products and processes.” (Barry and Christel, 2023) This emphasises the critical needs for design courses to actively involve disabled individuals as collaborators and creators in the design process. By including disabled creatives, it acknowledges their unique perspectives, experiences, and needs, which are often overlooked in traditional design education. Having disabled individuals as collaborators means that they are involved in the design process, offering insights, feedback and ideas that reflect their experiences and challenges.

“There is no disabled fashion, there is only fashion” (Annett-Hitchcock, 2024), this links to what Chloe Ball-Hopkins says in her TEDx Talk, ‘Why isn’t Fashion Inclusive of Disabled People?’, that “fashion should be inclusive not exclusive” (Ball-Hopkins, 2020). This shows that people within the fashion industry should be making clothes for all, not for abled groups. If the industry can change in the way they approach gender-neutral fashions in the retail market, the fashion industry should be able to adopt the same approach and “become ability-neutral” (Annett-Hitchcock 2024) moving forward. Annett-Hitchcock explained that she is surprised that after 20 years of her doctoral studies, people still hadn’t thought about the fact that people with disabilities need to wear clothes.

Delin summarises in ‘The Absence of Disabled People in the Collective Imagery of our Past’, that “Within museums, disabled people might not find a single image of a person like themselves – no affirmation that in the past people like themselves lived, worked, create great art, wore clothes, were loved or esteemed” (Delin, 2002: 84). I decided to search up disabled art, and there were very limited results that came up, but here is what I managed to find.

Figure 4

This is the first thing that came up, is a statue of Alison Lapper, who is pregnant, created by Marc Quinn. This sculpture was in the 4th plinth at Trafalgar Square. Quinn chose to make Lapper pregnant as a statue and he believed that the sculpture could be a monument to the future. In The Guardian article, Quinn commented, “Statue are of dead bloke. This is a living woman kicking arse.” (Jefferies, S. 2024) While other statues often depict historical figures, usually men, the statue of a disabled pregnant women symbolises inclusivity and celebrating everyday people overcoming challenges.

Figure 5

The British Museum also showcases a portrait of Mrs. Mary Morrell, an 18th-century woman born without arms. Depicted in a print by Robert Thew, engraver to the Prince of Wales, dated between 1778-1802. She is shown sat with her feet coming out from under her attire, adorned in fashionable Georgian clothing of the late 18th century. Mrs. Morrell enjoyed public recognition during her lifetime. This representation challenges stereotypes and highlights the visibility of disabled people in public life during that era. There is a ‘Nothing with us Without us’ exhibition at the people’s history museum, which explores the history of disabled people’s activism, ongoing fight for rights and inclusion. This suggests a growing awareness of the importance of including disabled voices and perspectives in discussions. The existence of this exhibition indicates that disabled individuals have been historically marginalized and excluded from decision-making processes, including creatives in fashion.

In essence, the intersection of fashion and disability is evolving. From historical representations challenging stereotypes to modern initiatives advocating for inclusivity, the progress in evident. Exhibitions like ‘Nothing with Us Without Us’ and brands like Tommy Hilfiger exemplify a growing recognition of disabled voices in fashion. The statement “There is no disabled fashion, there is only fashion” (Annett-Hitchcock, 2024) underscores the needs for inclusivity. Despite past marginalization, disabled individuals are increasingly visible and valued in the fashion industry. The ongoing fight for representation reflects a broader societal shift towards inclusivity, paving the way for a more accessible and representative future in fashion.

Bibliography

Adam, Hajo and Galinsky, Adam D (2012), ‘Enclothed cognition’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 48:4, p. 918-25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.008.

Annett-Hitchcock. Kate (2024), “The intersection of Fashion and Disability: A Historical Analysis” London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, p.7-209

Antrobus. Raymond (2018) “The Perseverance” Deaf Hearing World, p.38 Barry. B and Christel, Deborah.A (2023), ‘Fashion Education: The Systemic Revolution’

Ball-Hopkins. Chloe (2020) Why isn’t Fashion Inclusive of Disabled People? | Chloe Ball- Hopkins | TEDxBristol. Feb 7 2020. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jsMbrkl4OQ4&t=92s (Accessed May 13th 2024)

Brown. Robyn Lewis, Marato. Michelle Lee. and Pettinicchio. David (2024), ‘The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Disability’ p.217-220, New York, NY: Oxford University Press

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), (2020), “Disability and Health Overview”.Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html#:~:text=A%20disability%20is%20any%20condition,around%20them%20(participation%20restrictions)

Crane, D (1997). Globalization, organizational size, and innovation in the French luxury fashion industry: Production of culture theory revisited. Poetics, 24(6), 393-414

Delin, A. (2002), “Buried in the Footnotes: The Absence of Disabled People in the Collective Imagery of our Past”, in R Sandell (ed), Museums, Society, Inequality, 84–97, London: Routledge

Entwistle, J (2002). The aesthetic economy: The production value in the field of fashion modelling, Journal of Consumer Culture 2(3), 317-339

Figure 1. Photo by Victor VIRGILE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Figure 2. NSS staff, ‘Tommy Hilfiger’s new adaptive fashion collective’ (2021) Available at: https://www.nssmag.com/en/fashion/25701/tommy-hilfiger-adaptive-clothing

Figure 3, Evening Standard, ‘Asos are now selling specially designed clothes for people with disabilities’ (2018) Available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/lifestyle/fashion/asos-disability-model-a3879091.html

Figure 4, The Guardian, ‘Statues are of dead blokes. This is a living woman kicking arse’: how we made the fourth plinth’s Alison Lapper Pregnant’ (2024). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2024/feb/05/statues-are-of-dead-blokes-this-is-a-living-woman-kicking-arse-how-we-made-the-fourth-plinths-alison-lapper-pregnant

Figure 5. Portrait of Mrs. Morell, print made by Robert Thew, production date 1778-1902. Paper, stipple etching. Courtesy Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum, Registration number 1851,0308.453

Freeman et all. 1985) - Freeman, Carla. M, Kaiser, Susan. B, and Wingate, Stacey B. (1985), ‘Perception of functional clothing by persons with physical disabilities: A social- cognitive framework’, Clothing & Textile Research Journal, 4:1, pp. 46-52, https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302x8500400107.

Jefferies. S. (2024) ‘Statues are of dead blokes. This is a living woman kicking arse’: how we made the fourth plinth’s Alison Lapper Pregnant’ The Guardian. February 5th 2024. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2024/feb/05/statues-are-of-dead-blokes-this-is-a-living-woman-kicking-arse-how-we-made-the-fourth-plinths-alison-lapper-pregnant

Jessica Kellgren-Fozard (2016) Is Fashion Important to Disabled People? // Chronically Fabulous Life. May 5, 2016. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CDxyTa_4-sI (Accessed: May 13, 2024).

Lawson, M. (2021) 'Why Disability Representation Is Crucial to Building a Better, More Inclusive Fashion Industry', Vogue, March 10th 2021. Available at: https://www.vogue.com/article/why-disability-representation-is-crucial-to-building-a-better-more-inclusive-fashion-industry#:~:text=%E2%80%9CPeople%20have%20not%20seen%20us,authentic%20representation%20is%20so%20vital. (Accessed: May 13, 2024).

Mears, A, (2010). Size zero high-end ethnic: Cultural production and the reproduction of cultural in fashion modelings, Poetics, 38(1), 21- 46

Twigger Holroyd. A (2017), “Folk Fashion: Understanding Homemade clothes”, Identity, Connections, and the Fashion Commons, p.53, London: I. B. Tauris and Company.